In modern American society, generally speaking, labor is conceived of not merely as a professional responsibility carried out in the workplace, but as something far deeper. Work is an integral part of human identity, an activity that people can derive fulfillment from and in the absence of which some part of human nature is unsatisfied. As such, work has developed a recognizable culture of its own, varied as this culture may be across geographies and contexts. A key element of this American culture of work is that the act of labor possesses a distinctly spiritual quality, contributing something fundamental to the realization of the human telos. In this article, I contend that this spiritual quality finds its roots in Reformation theology, particularly in its Lutheran and Calvinist expression, which reoriented secular labor from being a tedious burden to a dignified vocation, or calling. Following the currents of Protestantism’s spread, this new conception of labor’s worth has come to exert considerable influence on how post-Reformation westerners, especially Americans today, conceptualize the value and role of work in our lives.

Medieval Christianity and the “Sacred-Secular” Categorization of Labor

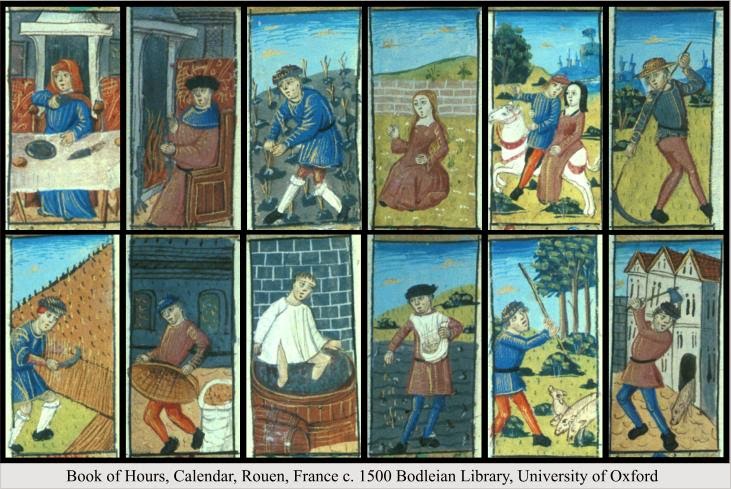

To appreciate the Classical Protestant view of labor as a dignified calling, we must first understand the status quo against which the Reformers responded. For more than a millennium prior to the Reformation, work was typically divided into two categories: sacred, which included clerical and monastic life, and secular, representing common occupations such as commerce, artisanship, and domestic duties to name a few. These two were divided not only by function but also by their spiritual value. See, for example, the dichotomy set up by the prominent church historian Eusebius of Caesarea (d. 339 AD) in his work Demonstratio Evangelica:

“Two ways of life were given by the law of Christ to his church. The one is above nature, and beyond common human living … Wholly and permanently separate from the common customary life of mankind, it devotes itself to the service of God alone … Such then is the perfect form of the Christian life. And the other, more humble, more human, permits men to … have minds for farming, for trade, and the other more secular interests as well as for religion … And a kind of secondary grade of piety is attributed to them.”

From Eusebius’ contrast between the “perfect form” of religious life and the “secondary grade of piety” enjoyed by those in the secular sphere, the lesser dignity given to common labor is evident. Of course—so this line of reasoning went—there must be Christians who work in secular professions, but they are limited in their ability to know and please God. This formed the dominant view of secular labor in the Medieval Church, even with scattered attempts to bring more spiritual regard to non-religious life. In this context, the “calling” or vocatio in Latin almost exclusively referred to religious life: one could discern whether God was calling them to the convent or ministry, language that Roman Catholics continue to use today. It appeared that God exercised greater concern for the religious professions of the Church rather than the ordinary, “secular” lives of other believers.

The Protestant Response

16th-century Reformers rejected this engrained dichotomy outright. Instead, they argued that secular labor was spiritually dignified and held intrinsic value equal to that of the clergy. They drew from many sources in their defense of this view. Their first evidence was of course Scripture. Common verses cited included Colossians 3:23 and 2 Thessalonians 3:11, which advocated respectively the dignity of regular work (even servitude) and the necessity of industry.

Systematic theological reasons were at play, too. Martin Luther’s (1483-1546) notion of the “priesthood of all believers,” which entailed that all Christians were in some sense priests before God, had the democratizing effect of eliminating the clerical class’s special status and sanctifying even the Christian’s mundane responsibilities. Some scholars have also pointed to differences in sacramentology, noting that whereas medieval Catholics viewed grace as irrevocably tied to the activity of the Church, Protestants recognized that God could also communicate His grace elsewhere. Where grace was no longer delimited by cathedral walls, it could enchant and sanctify the mundane, secular sphere—the farm, the workshop, the market street. Building upon Luther’s foundation was the Calvinist view of divine sovereignty and providence. According to the influential French theologian John Calvin (1509-1564), God was the “Governor and Preserver” of the universe, providentially “sustaining, cherishing, [and] superintending” all things. God’s absolute and naturalized providence also meant that He ordained through secondary causes each believer’s particular secular occupation. Calvinism’s soteriology (understanding of salvation) provided further substance to this idea. God had predestined certain “elect” people to salvation, and in the same way, also providentially “called” people to their respective professions. It was this predestinarian logic that provided the backbone to a transcendent, implicitly religious characterization of labor. Furthermore, if obedience to God was the telic end for a Christian, fulfillment of one’s calling was consequently indispensable to the realization of human potential, as a rational being created according to the image of God. We begin to see even in these early Reformers glimpses of a germinating culture of work.

Yet it was the New England Puritans, and not their continental ancestors, who articulated labor as a divine calling in terms more familiar to contemporary Americans. Having emigrated from England amidst religious and political persecution, the Puritans and their Calvinist successors busied themselves in establishing a society that placed industriousness front and center. Early on, the General Courts of Massachusetts and Connecticut passed legislation prohibiting idleness and the “neglect of men’s calling,” which could manifest in indigence, gambling, tavern-visiting, and more. Cotton Mather (1663-1728), the greatest of Boston’s clerical Mather dynasty, wrote extensively on the virtue, indeed the necessity, of prolonged work: “Yea, How can you Ordinarily enjoy any Rest at Night, if you have not been well at work in the Day? Let your Business engross the most of your time.” Mather was no hypocrite either: over his illustrious career, he produced over 300 published works (not even including his sermons)! Industrious effort in one’s calling was furthermore linked to joy and personal fulfillment. In The Religious Tradesman, popular author Richard Steele (1629-1684) recommended that “the tradesman’s shop or warehouse should be the place of his delight,” preferable even to his hobbies or leisurely country estate. Nonetheless, work was compulsory. The prominent Boston minister Charles Chauncy (1705-1787) was most clear in framing labor as inherent to human design, saying, “We were made for Business.” He doubled down further, declaring that work was the very “Law of Christianity.” The Puritans certainly found room for seasonable recreation and leisure, but diligent work was incessantly exhorted as personal, civic, and religious obligation. One can hardly discern the differences between Chauncy’s emphasis on labor as “Law” and the all-consuming hold that “economic productivity” has on corporate culture in the modern United States. It is no wonder that the phrase Puritan work ethic remains in steadfast use centuries after Puritanism itself has vanished, even if not from the American imagination.

These ideas, having been ingrained in the American psyche since the time of the Puritans through regulation, preaching, and culture, were transmitted and celebrated by subsequent Americans. The thrifty and industrious Poor Richard of Benjamin Franklin’s popular Almanac, or Horatio Alger’s rags-to-riches story line, or the celebrated idea of the American Dream, attest to this reality. Labor is not only virtuous and necessary to personal advancement, but an integral part of human experience and identity. The French political scientist Alexis de Tocqueville (1805-1859), in his work Democracy in America, captures perfectly the universality of this culture. “All honest callings are considered honorable,” and labor is “presented to the mind, on every side, as the necessary, natural, and honest condition of human existence.” The obsessiveness with which Americans view and practice work is no new phenomenon. It has instead been many centuries in the making. And it is rooted not in a secular, materialistic worldview, but the rich theological perspective of Reformation Europe.

Implications for Today

This awareness suggests the promising opportunity for retrieval: a retrieval of the theological heritage that underlies the now-secularized culture, or perhaps cult, of work. Writ large, modern America frames work as necessary to human wellbeing, and rightly so. But without the deeply spiritual reasoning that labor fulfills the divine mandate for activity, services others, stewards personal talents and cultivates human capital, and ultimately glorifies God, the incessance with which modernity promotes diligence leads instead to an empty workaholism—work for its own sake. The fruits of this loss are worrying and pervasive: hustle culture, endless self-improvement, and the inability to enjoy other gratifying spheres of human life. The unrelenting industry which we expect of ourselves must signify something more.

Leave a comment